“39 Songs that Shouldn’t Have Flopped but Straight People Let it Happen”

“42 Songs Only Gay People Know”

“30 Songs From the Early 2000s that only Gays and Woke Straights Know About”

These are just a few titles from popular pop culture website, Buzzfeed. I’ll give you a hint: close to none of the songs listed in these articles feature guitars or male vocals. That’s pretty much the gist of it. Apparently, if you’re gay, you only listen to dance/pop music from women who run the gamut of fabulous to glamorous, sexy to sultry–and everything in between. No nuance. No variety. Is that what it means to be gay?

According to Buzzfeed, it is. Don’t get them wrong: Buzzfeed loves gays, women, people of color, transgender people, disabled people–witnessed in all the articles they post that are usually on the right side of our current woke zeitgeist. Buzzfeed is nothing if not current in trends, that’s for sure.

Yet, they are curiously archaic in this innocuous tangent of articles written by gay authors themselves, that perpetuate the narrowest and most superficial gay stereotypes.

Why does a website that so clearly wants to appear enlightened allow such myopic fodder?

Maybe because articles about gay people who aren’t fun and flashy aren’t going to sell. Even gay people know that, which is why these gay authors write and sign their names on these frivolous pieces themselves.

Here’s the thing: it’s no secret that stereotypes are generally bad, but the open secret is that people often accept–even revel–in stereotypes they like, such as gay men’s alleged love affair with fun, disposable pop music.

Who cares if it’s a stereotype, when it’s oh-so-cool and flattering, depicting us as exciting, glamorous, and sexy? (Forget that these articles in question could also be accused of portraying us as: vapid, shallow, and superficial).

The main problem is though: obviously, not every gay person is like this. Even the authors (and readers) themselves probably know. Subsequently, when a gay person sees headlines and articles like these and doesn’t recognize themselves in them, it only perpetuates any nascent feelings of isolation and exclusion that are already too common among LGBTQA people–particularly young ones.

It’s ironic that in our current zeitgeist, which seems to multiply in identity politics by the year, month, day or hour, we can still perpetuate stereotypes like this so cavalierly–even diligently.

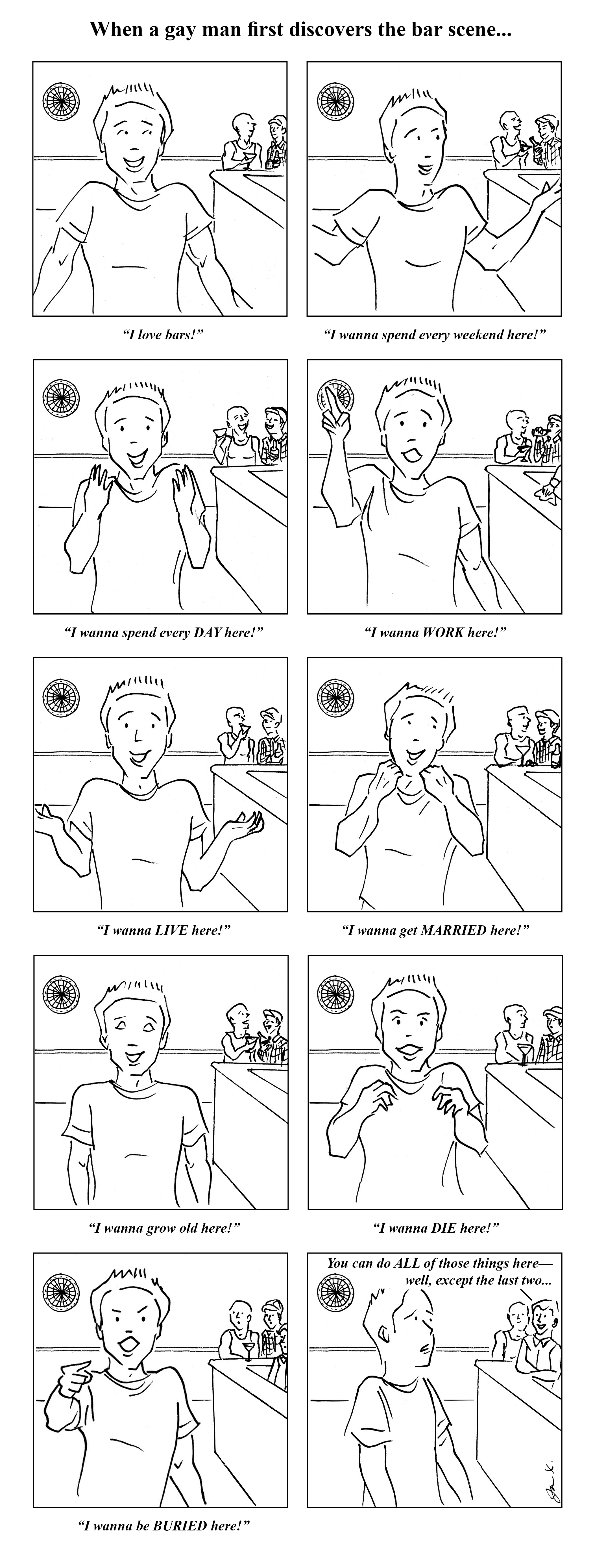

As any gay person knows, it’s still all too common to be judged by our gay peers for indeed not liking the latest Lady Gaga song or not idling our lives away at the local gay dance club.

Why do we still have these holdouts of ignorance, intolerance, and pressures to conform in the gay community, when we–along with the whole national zeitgeist now–allegedly preach enlightenment, tolerance, and acceptance of different lifestyles?

You do not get to pick and choose which stereotype is acceptable or not. It’s similar to double standards. You either reject them all or accept them all.

These articles are obviously not the equivalent of preaching hate, bigotry, or violence against anyone–but it’s no less damaging towards a community that still struggles to find acceptance and inclusion. Such articles offer too little to compensate for how much they can alienate.